This article originally appeared in Phayul.com on December 20, 2010.

http://www.phayul.com/news/article.aspx?id=28791

The conference on ‘Rethinking India’s Sino-Tibet’ policy affirmed that its time India look them (China) in the eye on Tibet issue.

New Delhi- The world’s largest democracy may be basking in the incontrovertible feat achieved in its 63 years of independence: its transition from a third-world developing country to its pioneering presence in the Non-Aligned Movement and also a super power in the reckoning, however when it comes to dealing with China, India’s Sino-Tibet policy remains apocryphal and a misfit in India’s otherwise paragon of virtue image.

Amidst reports of a staggering 60-billion-dollar business deal between the two Asian giants in the light of the three-day India visit by the Chinese premier Wen Jiabao and other trade deals galore, there is one area where India has faltered and failed miserably and that is in containing the ‘Sino-Tibet’ policy. Yes, this was the consensus emanating out of the December 15 conference: ‘Rethinking India’s Sino-Tibet policy’ organized by four Tibetan Non Governmental Organizations (Tibetan Women’s Association, Gu Chu Sum Movement of Tibet, Students for a Free Tibet, India and the National Democratic Party of Tibet) and held at the Casuarina hall, India Habitat Centre on the first day of India visit by Chinese premier Wen Jiabao.

The conference that took stock of complex − India-Tibet-China − triangular relations was chaired by Major General Vinod Saighal (Retd), the Executive Director of Eco Monitors Society (EMS) and author of the internationally acclaimed books including ‘Third Millennium Equipoise’ and‘Dealing with Global Terrorism: The Way Forward,’ Three keynote speakers addressed the conference; Jaya Jaitley, former president of Samata Party and a social activist, Tempa Tsering, minister (Kalon), Tibetan Government in Exile and the New Delhi representative of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Mohan Guruswamy, the Chairman and founder of Centre for Policy Alternatives and author of ‘Chasing the Dragon: Will India Catch Up with China?’

Coordinated by International Tibet Network, the conference saw an interesting audience composition; representations from India’s intellectual, policy-making, political and media quarters and few Tibetan activists.

At a time when India is in compelling situations created by China’s tremendous political, military, economical and geopolitical pressures on India, the speakers expressed scepticism in commenting on India’s acquiescence to China on the Tibet issue and demanded a stronger spine in India’s position.

History;

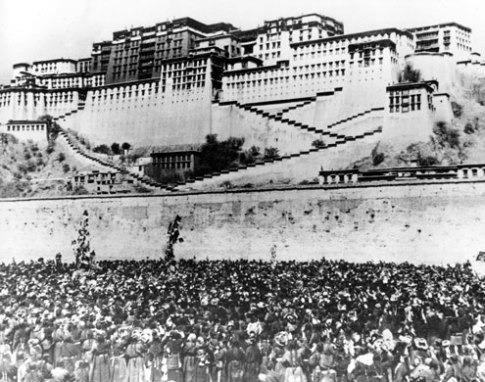

All the four speakers emphasized that historically China never was India’s neighbour and that Tibet was India’s neighbour and that it was Tibet who’s had relations with China albeit the equation kept vacillating from ‘being cordial to fighting wars.’

The Indian speakers lamented that there is no point castigating history as the inevitable fact of the matter is that ‘when China occupied Tibet, India could do nothing.’ “Inundated with the newly found independence and weakened by the partition, India was not in a position to take a realistic position on Tibet” reasoned Guruswamy. But it could be deciphered from the discussion that as the political landscape of the Himalayan region is beginning to unravel in the 21st century, the past history is a good indicator in discerning patterns of change in the future.

Border;

The conference stressed on the burning border rows between the two neighbours which is primarily because of the fact that from being an erstwhile effective buffer zone between China and India, Tibet’s 4000 km border now is place to world’s largest concentration of armed forces and military apparatus.

Jaya admonished the Indian government for skirting the issue of border security with China. “The ministry of external affairs is complacent in its posture where India has succumbed to the military dictatorship of its brutal neighbour” she said. Guruswamy added that the Indo-Chinese border is amorphous because ‘with Pakistan, India has a defined Line of Control which is essentially missing with China.”

Communist ideology;

Both Jaya and Guruswamy attributed the Asian fantasy with the rampant Communist insurgency in the early 1950’s as one reason why Asia failed to rebuke the Chinese occupation of Tibet. “Communism was converting Asia and India’s then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru himself was taken in by the soviet experiment” recalled Guruswamy. “People treated it as reform and change coming to Tibet,”

Jaya admitted that the communist thinking continues to dominate the Indian intellectual and foreign policy thinking. “When I was in the government, we realized that the policies of government were not run on issues of security but based on meekness and strange ideas of diplomacy which were dominated by communist thinking,” she recalled.

China’s greed;

While the Indian speakers labelled the encroachment into and the consequent annexure of Tibet by China as a murder, Kalon Tempa Tsering identified China’s greed for land and power. In recalling His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s hope for a genuine relationship between India and China, he commented “while genuine relation must be based on trust, China’s greed for territory, its insatiable taste for more land and its ambition to dominate and subjugate others and its unyielding stubbornness to hold to one-party rule are definitely not the basis for building trust and mutual confidence.” Kalon Tempa Tsering further added that ‘China’s never-ending rows with most of its neighbours are illustrative of its desires and designs’. He indicated that India’s restrained relations with its neighbours; Pakistan, Burma and Nepal, who, historically share a close cultural affinity with India, traces to the coerced instigation and incitement from China.

Commenting on the Chinese ambassador to India, H.E. Zhang Yan’s rhetoric remark that ‘the relationship between India and China is very fragile,’ Guruswamy berated ‘anything made of China is fragile.’

The panel discussion not only provided an in-depth overview of India’s 60 year old policy on Tibet, but identified the avenues and areas for India to make amends and do the thinkable; Re-Thinking.

Environment; The discussion dwelled on the one vital issue of Tibet that concerns India more than Tibet which is the massive rampage perpetrated on Asia’s water tower. The speakers ascribed Tibet’s environment to being crucial for the survival issue of India and the downstream nations. “China is building dams on the Brahmaputra and if India doesn’t voice out against this then the whole of north-eastern region of India could one day become a desert if India is deprived of the water flowing from Tibet’s glaciers” warned Jaya. She further added that ‘it is in India’s interest to see that Tibet’s grazing lands are protected and that Tibet’s waters are preserved.’

His Holiness the Dalai Lama;

The speakers enunciated on the dire need for a more realistic position by the Indian government on His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Kalon Tempa Tsering reiterated His Holiness’s proposal for a peaceful resolution on Tibet through the middle way approach. The Indian speakers conveyed that India has an imperative role to play in asking China to stop abusing him and in pressing the Chinese leadership to talk with him. Jaya complained that it is in ‘India’s acquiescence to have two yardsticks in dealing with His Holiness only as a spiritual head.’ She stressed that like every other leader, ‘His Holiness must be given the freedom to speak the exact words.’ “You always cannot have a man like the Dalai Lama to expect us to read between the lines,” she reasoned. Guruswamy stressed that India must strategize and prepare for a post Dalai Lama era. “Like the two Panchen Lamas it is foreseeable that there will be two Dalai Lamas”.

India’s identity;

The speakers bemoaned that ‘India is humiliated time and again by its ruthless neighbour and that there seems to be a mutual agreement that India is weak in its knees and that it has conceded to the Chinese atrocities.’ “When it comes to tackling the Tibet issue, we cannot take the backseat and be neck-deep in our own little pond, worried about our inner politics,” Jaya affirmed.

Jaya vehemently remarked that ‘India is negligent because of its sluggish bureaucracy and because it is intimated by the big and powerful neighbour.’ “This is one reason why China disrespects India” she said. Substantiating her point, Kalon Tempa Tsering advised that the Indian stand on China should be smarter considering ‘China’s respect for strength and power’.

On the issue of Chinese stapled visas issued to applicants from Jammu and Kashmir, Guruswamy gave a no holds barred comment that there is room for India for a tit-for-tat policy and suggested that India could start issuing stapled visas to several nationalities under the Chinese occupation. Commenting on the India’s foreign minister S.M Krishna’s recent remark -‘Kashmir is to India what Tibet and Taiwan are to China,’ Guruswamy’s deridingly spiteful remark ‘who will believe a man who hides his truth by wearing a wig?’ drew pearls of laughter from the audience.

The conference highlighted that it’s time for India to shed its elephantine firmness on its Sino-Tibet policy and that India can now no longer prevaricate on the Tibet issue which has hitherto been the mantra. The discussion underscored that it is time for India to ‘look them (China) in the eye’ and that there could be no better card then the Tibet card and no better opportunity then during the lifetime of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The discussion sternly stressed that tackling the Tibet issue is largely in India’s interest than in the Tibetan interest and that the perpetuating idling position of India will be ‘detrimental for the future of India—for its economy, security, ecology and for its very survival.’ The conference concluded that ‘a revised, stronger and strategic India’s Sino-Tibet policy will bolster India’s survival of its self respect and significantly its sense as a nation.’